From a design standpoint, some things just stand apart. They make you pause for reasons that go beyond looks — something about the form, the logic, or even the story behind them just feels right. Architects and designers notice these things because good design has a way of revealing itself, often in the simplest objects hiding in plain sight. Today, Andrew and I each picked a few of these objects that capture what makes design meaningful. Some have stories that are elegant, others a little chaotic, but all of them reflect the kind of thinking that keeps us fascinated by how things are made. Welcome to Episode 187: Objects of Design

[Note: If you are reading this via email, click here to access the on-site audio player] Podcast: Embed Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn

Today, Andrew and I are taking a closer look at a few things that hold meaning for us, and maybe, in some way, they’ll hold meaning for you too. The goal isn’t to create a list of favorites or convince anyone to like what we like. The real value comes from the story behind each object – how it came to be, why it mattered, and what it continues to represent. Those stories are what connect these designs to something larger than their purpose, and that’s what makes this conversation worth having.

The QR Code jump to 04:32

From Factory Floor to Everyday Life

Few objects have reshaped the way we live and work as quietly as the QR code. It’s a pattern so stripped of aesthetic ambition that most of us don’t even see it anymore – a matrix of black and white squares that hides a universe of information. The code was created in 1994 by Masahiro Hara, a young engineer at Denso Wave, a subsidiary of Toyota, who was tasked with solving a deceptively simple problem. Traditional barcodes could hold only a few dozen characters and had to be scanned one at a time. For an automotive supply chain that handled thousands of parts daily, that inefficiency was costly. Hara looked for inspiration outside his field and found it in the ancient board game Go – a grid-based system built on balance, contrast, and infinite variation. From that spark came the two-dimensional “Quick Response” code, capable of holding over 7,000 digits of data and readable from any angle, even if partially damaged.

But the real genius wasn’t just technical. It was philosophical. Denso Wave, though a Toyota subsidiary, decided that while they would patent the QR code to secure its authorship, they would not enforce the patent. Anyone could use it – freely, globally, and forever. In the 1990s, this was radical thinking. Corporate culture often defined success by ownership and exclusivity, yet Denso chose openness. Toyota saw the benefit of an industry standard that could streamline logistics far beyond its own factories. It was a gesture of quiet altruism wrapped in industrial pragmatism, and it changed the trajectory of digital communication. The QR code was never the property of a company – it was a gift from one engineer and one corporation to the world.

The Grid that Connects Us

As the technology matured, the QR code escaped the factory and began its migration into everyday life. It appeared first on shipping containers and inventory shelves, then on business cards, product packaging, and eventually storefronts. By the time smartphones became ubiquitous, it was waiting – ready to become the bridge between the physical and digital worlds. During the pandemic, its use exploded as touchless interactions became the norm. Restaurant menus, event check-ins, payment systems, and vaccination records all relied on that tiny grid. In a single decade, it went from a piece of manufacturing infrastructure to a global interface of trust and immediacy.

Its reach extends even into architecture and the building industry, where it has quietly become part of how we communicate space. QR codes appear on construction drawings, equipment tags, and site signage, linking directly to digital resources – specifications, BIM models, maintenance manuals, or installation videos. A single scan can reveal the entire data history of a mechanical unit or pull up a 3D detail that once required a stack of binders to locate. Architects now use them on presentation boards and project signage, connecting physical models to immersive walkthroughs or videos. On a job site, they turn static documents into dynamic systems of knowledge, democratizing access to information in a way that mirrors the code’s original purpose: speed, clarity, and accuracy in a complex environment.

Design as a Generous Act

Like all open systems, the QR code’s greatest strength – accessibility – is also its weakness. Because it can link to anything, it can also deceive. Malicious QR codes can redirect users to fraudulent websites, trigger unwanted downloads, or harvest personal data. In recent years, “QRishing” scams have emerged, exploiting that split-second of blind trust between scan and click. It’s a reminder that even the most neutral technologies inherit the ethics of their users. Still, the QR code endures because its core design remains sound. The responsibility now lies in how we frame its use – by combining better education, digital safeguards, and design transparency. For architects and designers alike, it’s a lesson in stewardship: even the simplest interface requires thoughtful intent.

The QR code deserves its place among the great objects of design not because it’s beautiful, but because it’s unfailingly useful. It represents the best kind of design thinking – elegant in logic, minimal in form, and generous in spirit. It bridges disciplines, generations, and geographies without needing translation. Masahiro Hara’s creation is a reminder that design’s highest calling isn’t ownership, but contribution. The QR code changed how we connect the digital and physical worlds – not through spectacle or branding, but through empathy and access. It is a perfect example of how even the smallest marks of design can have the biggest impact.

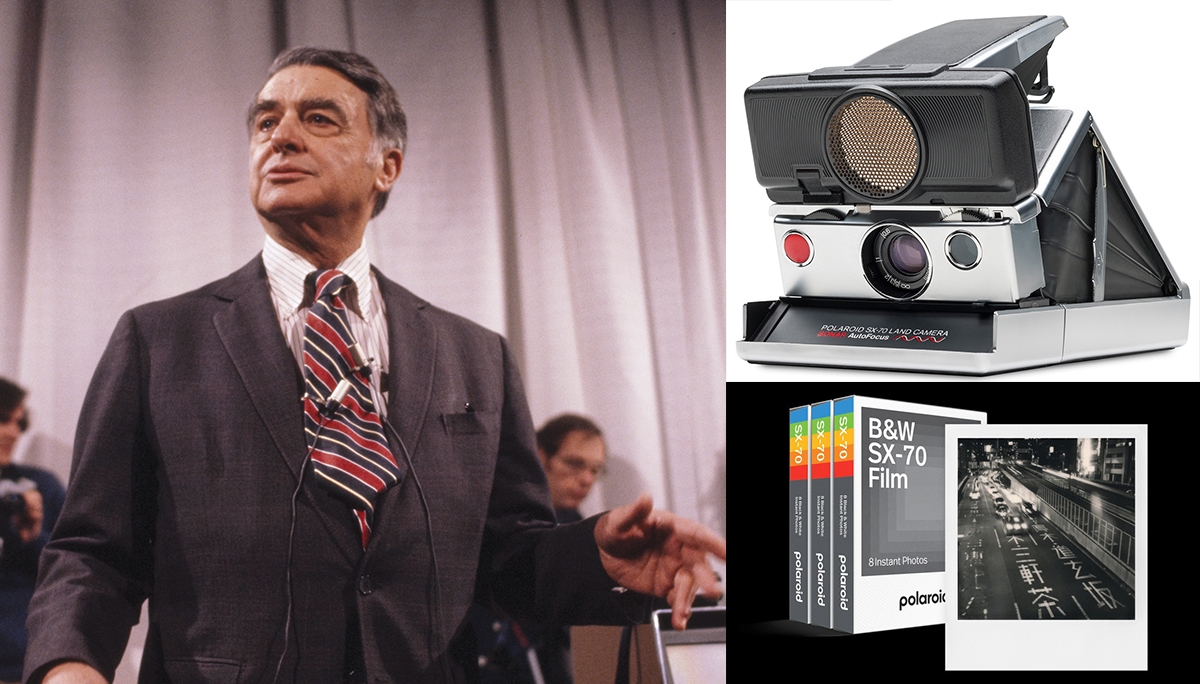

The Polaroid SX-70 Camera jump to 16:21

I remember this camera as a product in my house form my youth. While it wasn’t really “mine” in the sense of owning and operating it, I do recall it being used as my mother was a bit of an “amateur photographer”. So my first item is a Polaroid SX-70 camera. This was basically the first “truly instant” camera in the sense that it did simply required one to just take the photo and wait a few minutes for the film to “develop” right before your eyes. While it was not the first camera of this instant concept, its predecessors required additional work in separating layers of film coatings or other tasks to produce the final photo image.

In the history of designed objects, few capture both the promise and peril of invention as effectively as this Polaroid SX-70. The camera was a folding leather-and-chrome device that seemed less like a camera and more like a magical device when it first appeared in 1972. At the time of introduction, the SX-70 was touted as the most complex consumer object ever made. But the real story is not simply one of technological triumph, but also obsession, extravagance, artistic revolution, corporate rivalry, and eventual collapse. The story is as layered and complex as the seventeen chemicals required inside each Polaroid photograph it produced!

The Inspiration

The idea of the SX-70 was sparked decades earlier, in the 1940’s when, Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid, was questioned by his young daughter about why she couldn’t immediately see the photograph he had just taken. I laughed when first discovering this; thinking that the typical impatience of children is what helped push this entire camera system into existence! But Mr. Land, a pioneer in optics and chemistry, latched onto this question like a challenge. Why shouldn’t a photograph be developed instantly? This question became his life’s pursuit, for better or worse, pushing him and his company toward the invention of instant photography. Polaroid’s early attempts at “instant” were remarkable, but still sloppy. They consisted of peel-apart film packets, chemical coatings, and clunky devices that gave users messy fingers and inconsistent results. Land kept reaching for more. He wanted a camera product that produced a finished, color photograph in the time it took to shake someone’s hand. For most of his engineers, this was fantasy. For Land, it was the only option.

The Impossible Camera

What Land wanted was extraordinary and almost impossible at that time; a single system in which a pocket-sized camera, the film, and the development chemistry were fused into one seamless process. Each film pack would be a self-contained chemical factory, layers of emulsions and dyes waiting to react the moment the photo was “snapped”. The engineering hurdles this presented were immense and meant that seventeen distinct chemical layers had to remain inert until the moment of exposure, then flow precisely across the surface without leaking or smearing. Early prototypes were so fragile that technicians in lab coats assembled them by hand under near-sterile conditions. And these failed more often than they worked correctly.

The design mechanics of the camera were no less radical. Land wanted a reflex system with a bright viewfinder, yet he insisted that the body collapse flat enough to slip into a jacket pocket. Engineers had to design new plastics, complex gears, and folding bellows to make the device both functional and sculptural. Internally, Polaroid employees joked that an SX-70 film pack contained more sophisticated chemistry than the Apollo program. By the time the project neared completion, Polaroid had invested nearly $750 million dollars (in 1970’s) which is a staggering sum for a company of its size. This amount today would be the equivalent of $6 billion dollars of investment. Entire divisions were dedicated to Land’s vision. “Don’t undertake a project unless it is manifestly important and nearly impossible,” he told his engineers. The SX-70 became both.

The Reveal

When Land finally unveiled the SX-70 in April 1972 at a Polaroid shareholders’ meeting in Miami, the moment was staged like theater. He reached into his jacket, produced the slim leather-clad device, and snapped a picture of the audience. As they watched breathlessly, the small square of film ejected, white and blank and then, slowly, like magic, an image bloomed into being.

The crowd gasped. Some whispered as the colors deepened and sharpened. Land let them marvel. For years afterward, attendees described the experience not as a product demonstration but as something closer to a magic show. This set Land’s status to legendary.

Art, Parties, and Performance

The SX-70 quickly slipped beyond the world of consumer electronics and into the realm of culture. Andy Warhol hosted Polaroid parties where guests photographed one another, pinning the still-damp prints to the wall. David Hockney dissected and reassembled SX-70 images into sprawling collages, a photographic cubism made possible only by instant film. Even Ansel Adams, famous for his devotion to large-format photography, praised the SX-70 as a “new, refreshing instrument of expression.” You can see some of these examples from a Smithsonian Magazine post.

In 1972, Charles and Ray Eames were commissioned by Polaroid to produce a short film that shared the technical and emotional components for one of the most famous cameras in the history of photography. The film was first shown to Polaroid shareholders, and then later, it was used as a sales tool within Polaroid. If you want to watch… here’s the official Eames Office video.

For everyday users, the SX-70 democratized performance and mobility. Family gatherings, weddings, and street scenes all became a ritual activity consisting of the whir of the camera, the slide of the print, and the slow, magical reveal of the image. To experience this in everyday life, was not just memorable, but theatrical.

Fragility, Strain, and Downfall

But behind all this magic were plenty of problems. Early film batches faded quickly, their colors unstable. Prints cracked or yellowed within months, forcing Polaroid to quietly reformulate its chemistry. The camera was also expensive to purchase, $180 in 1972 (the equivalent of $1,200 today) and each film pack of only ten photographs added significant cost to use. The SX-70 was brilliant, but it was also fragile, elitist, and temperamental. Internally, Polaroid was stretched to a near breaking point. The massive investment in the SX-70 tied the company’s fortunes to its success. Land had staked his reputation and nearly his company on this one machine.

As Polaroid was celebrating, Kodak was watching. In 1976, Kodak introduced its own instant camera system, launching one of the fiercest intellectual property battles in corporate history. Polaroid sued, and after years of litigation, Kodak was forced to withdraw from the market and pay Polaroid nearly $1 billion. Yet the damage was irreversible. Consumers had been split, Polaroid’s finances were drained, and the market had shifted. The victory came too late to restore Polaroid’s dominance in the marketplace.

Then, by the 1990s, digital photography was beginning to rise, and instant film seemed quaint, slow, and “outdated”. Polaroid tried to adapt but simply could not. In 2001, the company declared bankruptcy. For many, the collapse of Polaroid was synonymous with the decline of analog memory itself.

The Legacy

Yet even in death, the SX-70 gained new life as myth. Designers and technologists spoke of it in reverent tones. Steve Jobs, who admired Land, later stated that Polaroid had been “Apple before Apple,” blending technology with artistry. When Polaroid shut down film production in 2008, a group of enthusiasts bought the last factory in the Netherlands and resurrected SX-70 film under the name The Impossible Project. The chemistry was imperfect, yielding prints with surreal colors and light leaks, but that imperfection became its appeal. The SX-70 had now come full circle; born as a miracle of control and now reborn as an object valued for its flaws.

Today, you can still purchase an SX-70 in refurbished forms and even occasionally as unused old stock. Also, Polaroid officially still makes the film packets for this camera. The Polaroid SX-70 was an elegant machine and marked an extraordinary moment in design history. It was at once a symbol of technological ambition yet also a cautionary tale of corporate hubris. It defied expectations, enchanted artists, drained fortunes, produced lawsuits, and (sort of) outlived its own demise.

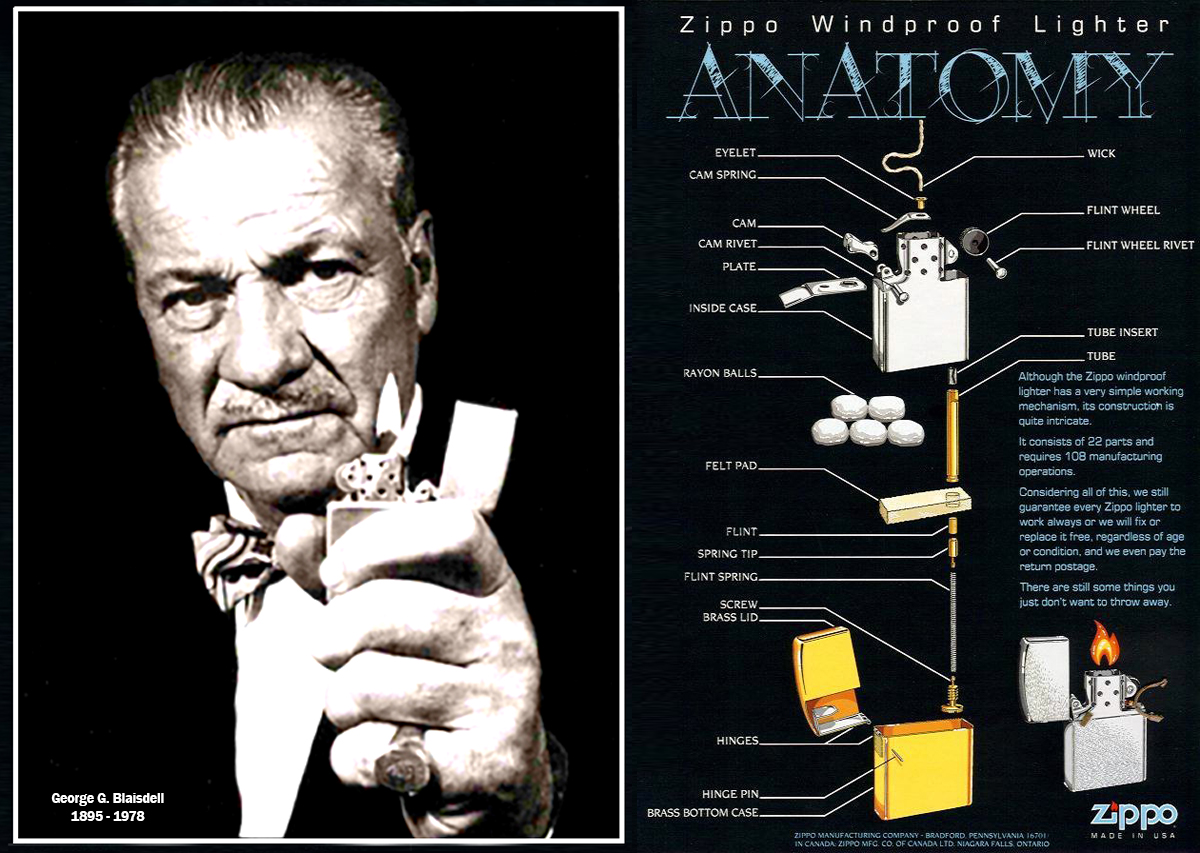

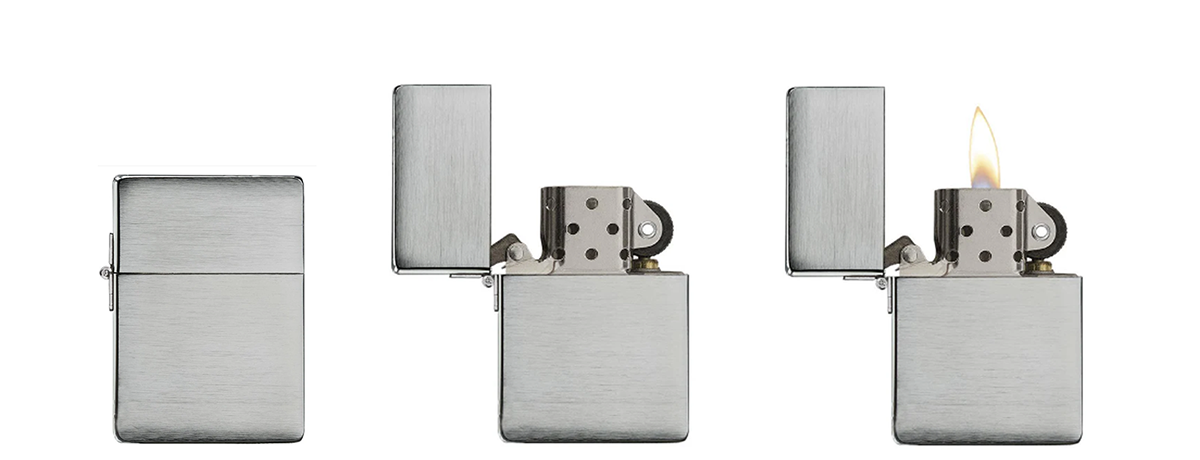

The Zippo Lighter jump to 32:47

The Fire We Carry

If the QR code represents the invisible side of design – digital, open, and altruistic – the Zippo lighter is its opposite. It is tactile, analog, and fiercely proprietary. Where the QR code democratized access by erasing ownership, the Zippo built its legend on identity and possession. One exists in the cloud, the other in your pocket. Together they form a kind of balance: two designs separated by nearly a century, both shaping how we connect to the world, one through data and the other through ritual. The contrast between them shows how design does more than solve problems; it defines relationships and influences how we interact with the tools we trust.

Function as Theater

Few objects have earned a place in both design history and pop culture like the Zippo lighter. It is an unassuming rectangle of metal, perfectly weighted in the hand, its lid snapping open with a sound that is equal parts utility and ritual. The Zippo was not born in a design studio or shaped by committee. It came from a moment of frustration. In 1933, George G. Blaisdell, a businessman in Bradford, Pennsylvania, watched a friend struggle with a clumsy Austrian lighter that required two hands to operate. Blaisdell saw the problem instantly: poor ergonomics, bad wind protection, and no grace in use. Within months, he had redesigned it with a hinged lid, a chimney-style flame guard, and enough mechanical precision that a single flick of the thumb brought it to life.

That mechanism, part engineering and part theater, is what made the Zippo timeless. It was not just a lighter; it was a performance. Soldiers carried it into battle during World War II, flipping it open with one hand while clutching a rifle with the other. The lighter’s reliability and windproof design turned it into a small symbol of control in a world where almost nothing was guaranteed. Zippo stopped civilian production during the war to focus exclusively on supplying the military, and in doing so, created an identity that would outlast its utility. When those soldiers came home, they brought the ritual with them. The click, the spark, and the pause before the inhale followed them into the American imagination.

Blaisdell understood something about design that most manufacturers did not. People do not form attachments to things that simply work; they connect with things that feel like they will always work. Every Zippo came with an unconditional lifetime guarantee: “It works or we fix it free.” That promise nearly bankrupted the company in the 1950s, but Blaisdell refused to abandon it. He was not selling a product; he was selling trust. In an era of disposable goods, that made the Zippo radical. Even today, you can send one back to Bradford and someone will repair it by hand with no questions asked. It is craftsmanship turned into customer philosophy, functional design elevated by accountability.

Designing a Myth

The Zippo story is not without its share of mythology. The company promoted the idea that every Zippo carried a personal story, that every one of them had “seen action.” It was not true, but that did not matter. The lighter became a prop in countless films, an accessory for icons from James Dean to Andy Warhol, and a fixture in American design symbolism. The brand blurred the line between fact and legend until the two became indistinguishable. In that sense, Zippo did not just design a product; it designed a myth, a narrative that keeps an obsolete object culturally alive.

Architects, perhaps more than most, understand the tension between permanence and performance. The Zippo’s beauty lies not in its polish, but in its purpose, a perfect example of form following function where every edge, hinge, and proportion is dictated by need. Yet the real story is how something so purely utilitarian transcended its function. It became proof that design can outlive its relevance when it captures something deeper: a ritual, a rhythm, a feeling of control in an unpredictable world. The QR code connects us to information. The Zippo connects us to memory. Both, in their own way, remind us that good design does not age … it endures.

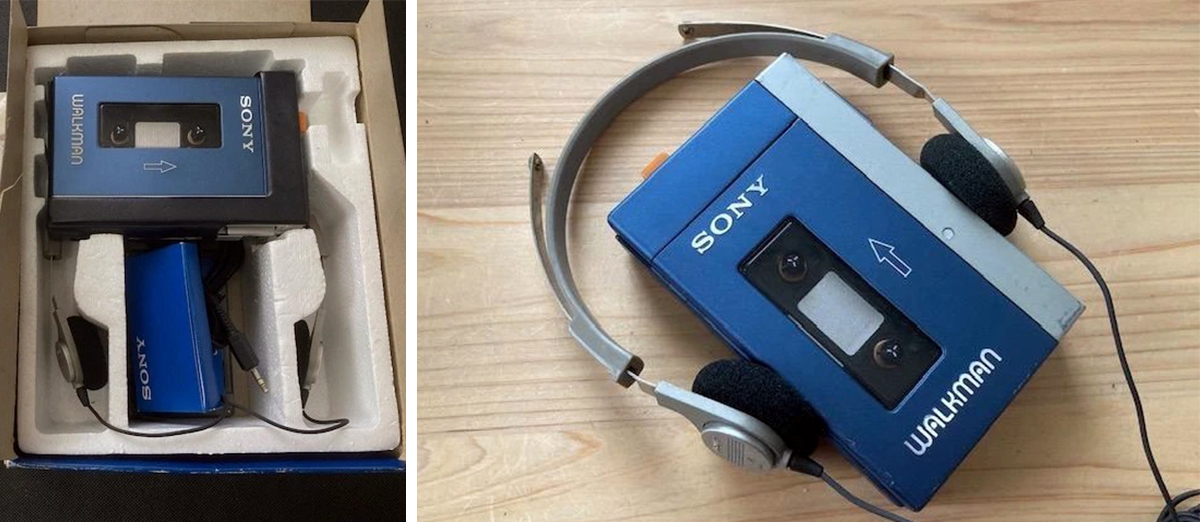

The Sony Walkman (TPS-L2) jump to 41:37

My second object is also one that drastically changed the landscape of its product arena, and things were never the same. Similar to my first object, this one established a level of individualization and freedom never before seen for its industry. The Sony Walkman was initially launched in 1979 as the TPS-L2, a small blue-and-silver cassette player about the size of a paperback book. This device transformed listening forever. Music, once tethered to the living room or the car, suddenly became portable, private, and omnipresent.

Origins in a Stripped-Down Recorder

The Walkman’s invention came from a simple request by Sony co-founder Masaru Ibuka, an opera enthusiast, who wanted a portable way to listen to opera on business trips. He turned to Sony engineer Nobutoshi Kihara, who developed a solution almost entirely based on existing Sony technology. He modified the Sony Pressman, a portable cassette recorder, by removing the microphone and recording circuitry, adding a lightweight stereo amplifier, and pairing it with foam-covered headphones. The result was compact, light, and unlike anything else on the market by being dedicated to playback alone.

At first, Sony executives balked at the idea of sales. Why would consumers want a tape player that couldn’t record? Yet Sony’s gamble would prove to be transformative. The product’s greatest strength became that it was built entirely for the pleasure of listening.

Roller-Skates and Original Features

Sony knew the product would be unfamiliar and needed a bold launch. For the Tokyo debut, the company staged a very public stunt. They hired employees and models to roller-skate and skateboard through the city with Walkmans on their belts, stopping random pedestrians and placing headphones on their ears. People were mesmerized. The sensation of private music in public space was so novel for people to feel firsthand. The first model, the TPS-L2, included two headphone jacks and a bright orange “hotline” button, allowing two listeners to share music and briefly allow in outside voices. This hotline feature was rarely used and soon dropped, as was the secondary headphone jack. Ironically, a device introduced with the notion of sharing the experience became synonymous with solitude, being remembered as the object that made listening to music a completely private act.

Even its name was a process of elimination. Inside Sony, engineers jokingly called it the “Walkman,” a piece of awkward Japanese-English translation that executives considered embarrassing for exporting. So, early U.S. units were branded as the “Soundabout,” and in the U.K. as the “Stowaway.” But consumers ignored those substitutes and asked for “Walkman,” causing the undesired name to stick. By 1986, Sony gave in and embraced the “Walkman” label worldwide. What Sony feared would sound ridiculous, instead, became one of the most iconic product names in design history.

Cultural Shockwaves

The Walkman rapidly reshaped how people experienced public life. Commuters, joggers, and teenagers now carried their own soundtracks, creating what sociologists called a “personal auditory bubble.” The city became less chaotic and more controllable, as filtered through music.

For many, this was liberating. The Walkman gave individuals power over mood, tempo, and atmosphere in their daily lives. For others, it was disturbing. Critics accused the Walkman of breeding antisocial behavior. In 1981, The New York Times lamented that users were “plugged into themselves and tuned out of society.” Public officials raised safety concerns, and several U.S. states debated bans on headphone use by pedestrians and cyclists. Many did ban their use in certain instances. Urban legends circulated about distracted teens stepping into traffic, but whether this is true or not remains uncertain. The Walkman quickly became shorthand for dangerous distraction. For me, this rings very similar to conversations today about mobile phones.

Fashion, Politics, and Cold War Symbolism

Sony never marketed the Walkman as a basic piece of electronics. It was always styled as an accessory. Early models came with belt clips, wrist straps, and leather cases. Design variations followed the logic of fashion seasons, featuring bright plastic models for youth and sleek metallic finishes for executives. By the mid-1980s, magazines featured the Walkman in style spreads alongside sneakers and sportswear. It was as much about how it looked within your personal style as how it sounded in your ears.

The Walkman arrived at a time when the boombox dominated public city streets. The two devices represented opposite philosophies: one blasting music outward, communal and public, and the other bringing music inward, solitary and private. Some saw the Walkman as a civilizing force, quieting the clamor of public sound. Others saw it as a retreat into selfishness. In either case, it redefined how sound existed in shared space.

The device also acquired unexpected political weight. In Eastern Europe, smuggled Walkmans became black-market treasures, symbols of Western modernity. Rumors circulated that governments feared cassette tapes could transmit “portable propaganda.” To carry a Walkman in the Eastern Bloc was not just to own music but to signal rebellion, cultural defiance, or even an indication of spy craft.

Peak Popularity and the Fall

By 1986, “Walkman” had entered the Oxford English Dictionary. By 1989, more than 50 million units had been sold. The device was everywhere. It could be seen on joggers, on subways, in bedrooms, in schoolyards, and in all other imaginable locations. Owning a Walkman was almost a generational marker, a passport into youth culture. But its success also masked its fragility. By the 1990s, music was shifting to digital. Sony clung to physical formats, investing in MiniDisc and ATRAC, and hesitated to embrace MP3 players. Its ties to the music industry made executives fear piracy, a caution that ultimately cost the company. When Apple released the iPod in 2001, it seized the cultural territory the Walkman had pioneered. Sony, once synonymous with portable sound, had been overtaken. Again, like Polaroid, by clinging to their best-selling product and technology, they allowed others to usurp their market dominance.

Legacy of a Portable Revolution

Despite its inevitable decline, the Walkman’s influence was astounding and enduring. It normalized the idea that music could be personal and mobile, a constant companion throughout your day, no matter the situation. Every pair of earbuds, every smartphone playlist, all trace their lineage to that blue-and-silver box from 1979.

The Walkman was also wrapped in contradictions that make it a fascinating design object. First, it was launched with a sharing function, yet it is remembered for its proliferation of solitude. Second, it was accused of isolating society, yet it gave individuals unprecedented control. Lastly, it was originally resistant to its name, which became one of the most recognizable in the world.

The Sony Walkman is best understood not just as technology but as a story of invention, skepticism turned into infamy, and unintended cultural liberation. In its lifetime, the Walkman became not just an electronics success but a cultural phenomenon that redefined how people moved through the world. Above all, it is the story of how a small, unassuming object reshaped not only how we listen to music, but how we live our lives, even to this day.

Hypothetical jump to 49:38

We haven’t had a true hypothetical question in a while, and this one (kinda) comes from my daughter Kate.

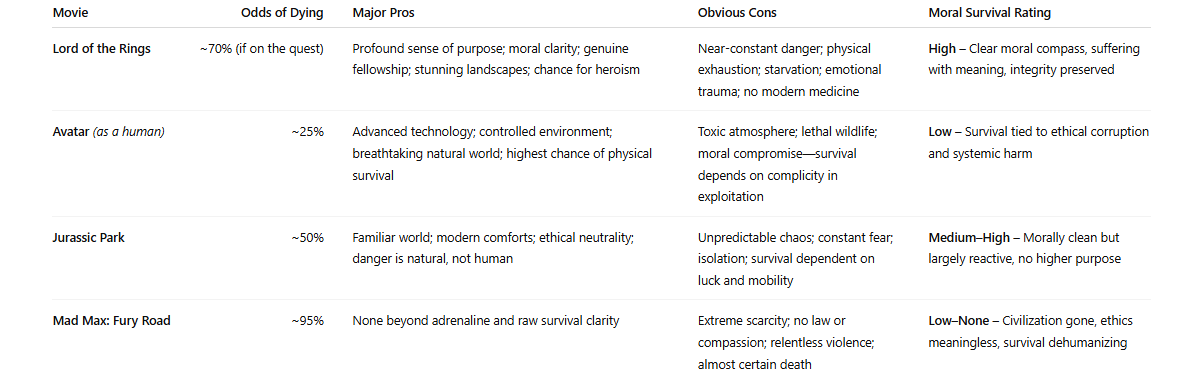

You’re about to be teleported into the world of a movie for an entire year. You don’t get superpowers, special gear, or a guarantee you’ll make it out alive – you just show up as you. So, where are you taking your chances?

- Lord of the Rings – you have to go on the quest so … the terror of Mordor

- Avatar – Gorgeous, glowing, and full of creatures that want to kill you.

- Jurassic Park – You’re told the fences are working… until they aren’t.

- Mad Max: Fury Road – No water, no rules, just hope your car starts.

I will tell you that my twist to this question is that it isn’t just about survival, how you emerge on the other side of a year is part of this equation.

Episode 187: Objects of Design

Good design lasts because it continues to matter. The best objects find balance between purpose and experience, where function and emotion share equal weight. A thoughtful design solves a problem while creating a connection, encouraging people to keep it, repair it, or discover new uses over time. Enduring work often begins with necessity or curiosity, but it is sustained by clarity and conviction. Lasting value is not driven by fashion or technology, it comes from the strength of an idea and the confidence that it was made well from the very beginning.

Cheers.

“Special thanks to our sponsor Construction Specialties, maker of architectural building products designed to master the movement of buildings, people, and natural elements. Construction Specialties has been creating inspired solutions for a more “intelligently built” environment since 1948. Visit Mastering Movement dot net to learn more.”