The idea of an architect designing a house for themselves sounds inevitable, like it’s lurking on the horizon as some kind of professional rite of passage. Reality doesn’t line up with the expectation, and not because architects lack the skill or the opinions. Most people assume this would be pure freedom, but the moment the project becomes personal, it picks up a strange kind of weight, including the quiet sense that the result will be read as a statement whether it was intended that way or not. Public judgment sneaks in through innocent questions and raised eyebrows, since everyone seems to think a home should prove something about the person who designed it. Constraints still exist, of course, and the ones that hurt the most tend to be self-imposed. Welcome to Episode 195: Designing Your Own House.

[Note: If you are reading this via email, click here to access the on-site audio player] Podcast: Embed Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | TuneIn

Today we are going to be talking about architects designing their own house. This is not about “how” to design your house, today’s conversation will focus on this on why it’s so hard, as well as what matters.

The idea that an architect should eventually design their own home hangs around the profession like an unspoken credential, something people assume is inevitable once you’ve been doing this long enough. The expectation is usually delivered casually, but it carries weight, particularly when the person asking has already decided the answer says something meaningful about you. The pressure lands differently depending on what kind of architect you are, and the world tends to ignore that distinction because nuance is inconvenient. Architects who design houses for a living get evaluated through a different lens because their home reads like a permanent portfolio piece. Clients and builders, neighbors and other architects, all have the same quiet question in the background: if you do this professionally, what did you choose for yourself? Judgment rarely shows up as criticism, since most people prefer polite curiosity to honesty, but it still works the same way. People interpret the house you live in as a reflection of your taste, your priorities, your competence, and your confidence, even though real life usually has the nerve to involve schools, commutes, relationships, timing, market conditions, and the small detail that the house you ended up in was the one that existed when you needed one.

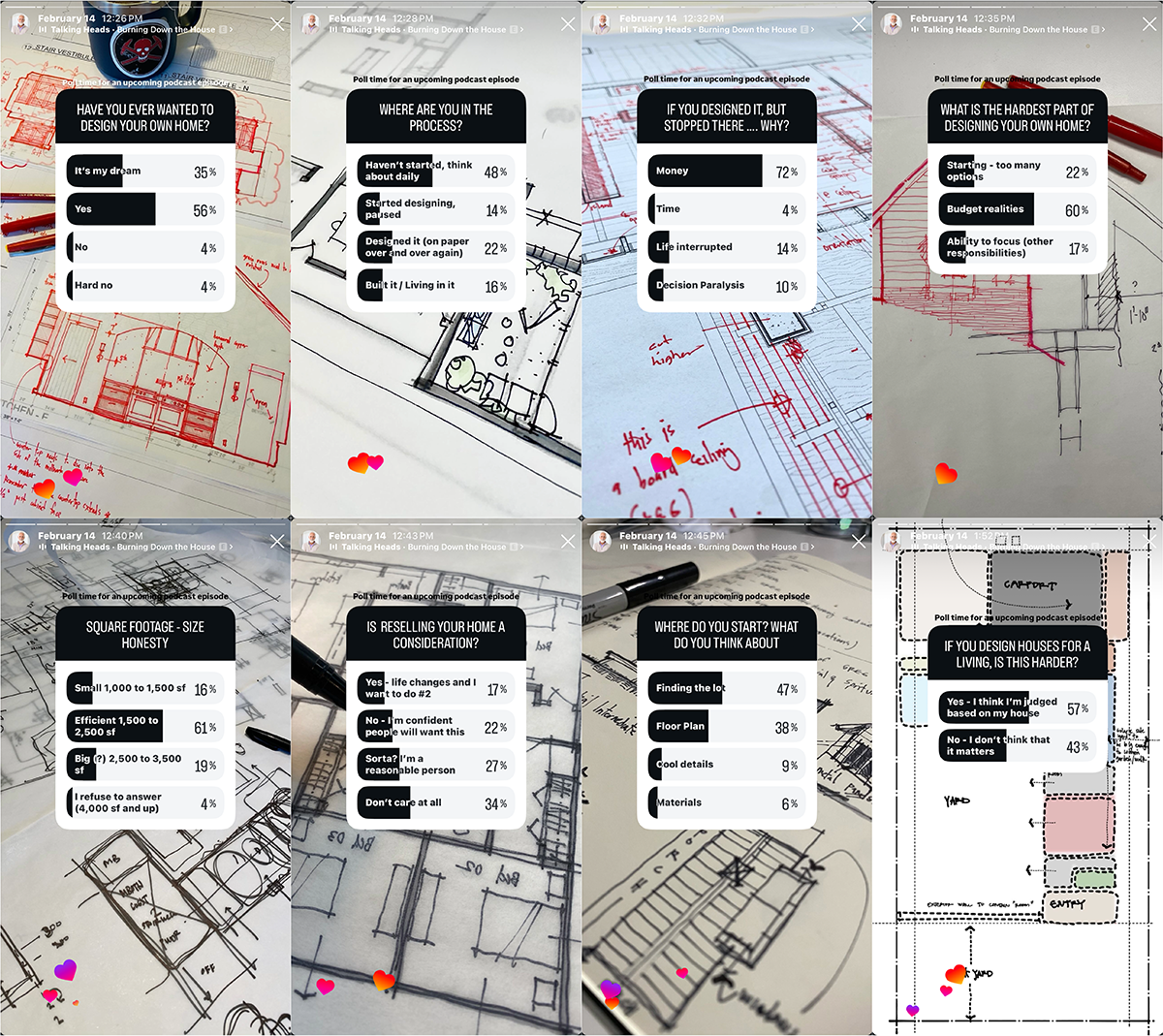

I did a poll on Instagram and the results were not all that surprising …

The Myth of Designing Your Own House jump to 23:30

The myth starts with a clean assumption: that designing your own home is a singular, definitive act that results in a permanent statement of who you are as an architect. That assumption is attractive because it turns a complicated topic into a neat story with a satisfying ending. A personal house becomes the ultimate reveal, the moment where everything you believe about proportion, light, material, and craft shows up at full scale without interference. The problem is that the premise only works if life holds still long enough for the “final answer” to exist. Life doesn’t. Designing your own home is not a fixed target, and the house you would design at thirty-five is not the house you would design at fifty-seven. Budget shifts, energy shifts, priorities shift. Children change the program, and the age of those children changes it again. Work changes, relationships change, bodies change. The myth pretends the house is the point. The reality is that your life is the point, and the house is simply the response you can afford, manage, and tolerate at a given moment.

Residential architects feel the myth differently because they live inside a constant comparison loop between what they know and what they can actually fund. Years of designing other people’s homes builds a catalog of what’s possible and what’s meaningful. Knowledge that should feel like an advantage turns into friction when every decision comes with a better version you can describe in exact detail, price with grim accuracy, and still choose against because the math refuses to cooperate. That gap between expertise and affordability is not theoretical. It’s personal, and it makes the act of “designing your own home” feel less like freedom and more like a negotiation with yourself. Another reality sits under all of this, and it’s one the myth refuses to acknowledge: not every architect is a designer. Plenty of architects are exceptional at the work that makes buildings real, durable, and buildable, and self-awareness tends to arrive around the same time the profession expects you to produce some kind of personal statement. The myth assumes everyone is trying to build a monument. Most people are trying to build a life that functions, and for a lot of architects, that’s the more honest and more difficult work.

The Paralysis of Choice jump to 31:48

Designing your own home sounds like it should be easier than designing anyone else’s. The logic feels obvious: you know what you like, you know how you live, you have a personal stake in getting it right. That tidy little assumption evaporates the second you realize that being your own client removes the one thing that keeps most projects moving forward: a clear external filter. Clients, for all their quirks, provide boundaries. They supply the non-negotiables, the must-haves, the deal-breakers, the things they will fight for and the things they truly do not care about. That friction can be annoying, but it also gives the work shape. When the client is you, the shape gets fuzzy. Every preference is negotiable, every idea is plausible, and every decision comes with a nagging voice that says, “If you’re doing this for yourself, shouldn’t it be better than that?!?” The result is a weird kind of paralysis that doesn’t come from not knowing enough. The paralysis comes from knowing too much, seeing too many options, and being unable to unsee them once they show up. Choice becomes the problem, not the solution, because infinite choice turns the act of designing into an identity exercise instead of a problem-solving exercise.

The trap is that every option branches into consequences, and you can’t pretend you don’t understand the downstream effects. A window is never just a window. A window is orientation, heat gain, glare, privacy, furniture placement, wall space, budget, structure, waterproofing risk, and the joy or annoyance you will feel every single day for the next decade. A material is never just a material. It’s maintenance, aging, repairability, cost volatility, availability, labor skill, and whether it will look good in five years or just look like you got caught up in a moment. Even simple choices get heavy when you realize you’re not deciding what looks good on paper, you’re deciding what you will live with when you’re tired, distracted, stressed, sick, or hosting people you like less than you intended. No project review is coming to save you. No client meeting is going to clarify the priorities. The only person who can define what matters most is you, and that turns out to be harder than it sounds. Designing your own home asks a question most architects are not used to answering directly: what do you actually need, and what are you just attracted to? The paralysis lifts when you stop trying to design the best possible house and start designing the right house for the life you actually have, which is less glamorous, more honest, and annoyingly difficult to do with a straight face.

Ego versus Need jump to 38:52

Designing your own home forces a blunt decision that most projects let you soften with diplomacy: is this house a statement about you and your abilities, or is it primarily a place to live. The profession pretends those two things naturally align, like good design automatically equals good living, and like personal expression always produces better rooms. Reality is less cooperative. A personal house is the one project where every move can feel like evidence. Window placement stops being “a good solution” and starts reading like “your taste.” Material choices stop being “appropriate” and start reading like “your priorities.” Even restraint becomes performative, because a quiet house can be interpreted as confidence or as a lack of imagination, depending on who’s looking and what mood they’re in. That external reading matters more than anyone wants to admit, especially when the people doing the reading understand the game. Other architects see intention everywhere, even where none exists. Clients see your house as proof-of-competence, even though competence rarely dictates the school district you needed, the timing you were stuck with, or the mortgage rates you had to tolerate. A personal project becomes a strange mirror, because the design decisions are not just design decisions anymore. Those decisions start carrying the weight of reputation, identity, and the kind of professional self-image nobody talks about in a healthy way.

Budget turns that question from philosophical to painfully specific. Money is not just a constraint, money is a spotlight. Every dollar you spend becomes a statement about what you think matters. A grand gesture is rarely “free,” even when it looks clean and effortless. Double-height spaces, long spans, dramatic stairs, massive openings, indoor-outdoor transitions that actually work, all of it costs real money, and the cost usually shows up in places you would rather not sacrifice. Kitchens become battlegrounds because they are expensive and visible. Bathrooms quietly eat budgets because water is chaos and complexity has a price. Windows feel righteous until you price the good ones. “Cool details” sound romantic until you remember the difference between a detail that photographs well and a detail that gets executed well by normal humans in the real world. Priorities show up in what gets protected when the budget starts tightening. Some people protect the big move and let finishes fall into “good enough.” Some people protect durability and let the architecture stay quieter. Some people spend on the envelope because they are tired of pretending energy performance is optional. Some people put the money into the spaces they use every day and let the guest areas be politely ordinary. None of those approaches are wrong, but each one reveals something. A personal house makes you answer questions that clients usually answer for you: which problems deserve the money, which problems get solved with ingenuity instead, and which problems you are willing to live with because solving them would cost too much, take too long, or demand more attention than you have left.

A statement house can be honest and great, provided the statement is clear about what it sacrifices. A livability-first house can also be honest and great, provided the restraint is intentional instead of defensive. The real mistake is designing for an imaginary jury and then pretending the outcome is purely rational, because nobody believes that, least of all you. The useful framing is simple: the budget will not let you express everything, which means the house will reveal what you value most, whether you want it to or not.

Money Changes Everything jump to 46:08

Money is the part of this topic that everyone tries to treat like a footnote, mostly because it makes the conversation less romantic and more honest. When people are asked why designing their own home hasn’t happened, money shows up first and it shows up by a lot. Another layer sits under that answer, and it’s the one that feels especially familiar: enthusiasm tends to arrive early, while financial capability tends to arrive later, if it arrives at all. Early in a career, energy is high and ideas are plentiful. Taste is forming, confidence is rising, and there’s a genuine hunger to make something that feels personal and intentional. The problem is that early-career money is not built for land purchases, construction loans, and the kind of contingency that keeps a project from becoming a prolonged panic attack. The gap between desire and capacity becomes the first real constraint, and it’s not just a practical issue, it’s a timing issue. The home that feels “right” in the mind during that enthusiastic phase is often tied to a version of life that doesn’t exist yet, or won’t exist for long. The longer it takes for the finances to catch up, the more likely it becomes that the original motivation shifts. That shift isn’t failure. That shift is life happening.

By the time the financial side starts to look plausible, the inputs may have changed so much that the original concept no longer fits. Careers evolve, relationships evolve, kids arrive or leave, health becomes more present in daily decisions, parents age, priorities get reordered by events that don’t ask permission. Even the idea of what “home” means can move from aspiration to comfort, from statement to shelter, from space to simplicity, from novelty to durability. Financial capability arriving later can feel like winning a race only to discover the finish line was moved a mile back and the route is different now. Market conditions add another layer of unpredictability, since affordability isn’t just personal income. Interest rates, labor costs, material pricing, and land availability all shape what can actually happen, and those forces are indifferent to enthusiasm. Money forces prioritization, and the hardest part is that priorities are never static across decades. A personal home isn’t one decision made once. It’s a decision made in the context of a moving life. The real challenge isn’t only getting enough money to build something. The real challenge is arriving at the moment when money, timing, and the version of life being lived all align closely enough that the project still makes sense.

Emotional Exposure jump to 53:33

Designing for a client is professional, which is another way of saying the work comes with built-in distance and structure that keeps decisions from feeling overly personal, even when the stakes are high. Priorities get stated, budgets get set, and the push and pull of the process creates a natural filter that keeps things moving, because there’s always a clear question sitting underneath the discussion: what best serves the client’s life. Myth, infinite choice, the temptation to make a statement, and the reality of money still exist in client work, but they land in familiar places. Myth becomes expectation that can be managed through communication. Choice becomes a problem to solve through process. Statement becomes a preference to calibrate. Money becomes a constraint that can be negotiated with scope. The professional framework doesn’t remove difficulty, but it does distribute it. Responsibility is shared, decisions can be tested in conversation, and even compromises have a place to land because they belong to a collaborative process rather than a private reckoning.

Designing for yourself is autobiographical, because the same decisions stop being abstract and start describing the person who made them. Layout becomes routine, circulation becomes habit, and adjacencies become preferences drawn into permanence. Storage becomes a measure of tolerance for disorder, and light becomes something closer to mood management than aesthetics. Privacy becomes a statement about boundaries, while openness becomes a statement about togetherness, and neither of those things is neutral once they’re embedded into walls. The earlier sections converge here, but not as a conclusion to the whole conversation, more like a spotlight that finally shows what has been driving the tension all along. Myth creates the expectation that the house should say something. Infinite choice makes every decision feel meaningful. Statement versus shelter turns design into a question of identity. Money forces priorities to declare themselves. Emotional exposure is what’s left when all of that pressure points inward, and the work stops being about producing a good house in theory and becomes about telling the truth, quietly and permanently, about how life is actually lived.

Ep 195: Designing Your Own House

Designing your own house sounds like the kind of project architects should eventually take on, yet the closer it gets, the more complicated it becomes. Personal work removes the professional buffer, which means every decision carries a little extra weight, even the ones that seem minor on paper. The process forces priorities to declare themselves, because not everything can be protected, afforded, or justified at the same time. The temptation to make a statement is real, and the quieter challenge is making sure the house still supports the life happening inside it. Plenty of architects discover that the hardest part isn’t drawing the plans, it’s deciding what matters when the client, designer, and critic are all the same person. The goal isn’t perfection, it’s honesty, and maybe a little peace with the trade-offs.

Cheers,

Special thanks to our sponsor Construction Specialties, maker of architectural building products designed to master the movement of buildings, people, and natural elements. Construction Specialties has been creating inspired solutions for a more “intelligently built” environment since 1948. Visit MasteringMovement.net to learn more.